By Belinda H.Y. Chiu

22 July 2022

As we noted in the first of this series, the Compassion Strategy includes:

- Centeredness: intentional focus + purposeful play + active agency;

- Courage: authentic integrity + healthy conflict + compassionate candor; and

- Curiosity: shared connection + improvisational paradox.

This strategy enables leaders to leverage the Three-Box Solution for the health of their teams and the greater good. Doing so inspires others to trust and follow them, which strategy expert Vijay "VG" Govindarajan notes is an ability of leaders to: 1) manage the present; 2) selectively forget the past; and 3) create the future. Sustaining such a level of awareness and keeping the organization moving through change while staying curious, open, and adaptable requires centeredness, intentional focus, and agency, with a proclivity for play.

Intentional Focus

First is intentional focus. Despite the best intentions, many leaders find themselves locked in a myopic focus on the specifics of how to achieve a 30-year strategic goal or why something failed. The most effective leaders, particularly during times of crises, know when to zoom in and get into the details and when to zoom out and take a 30,000-foot view, often at an imperceptible speed. After all, every in-the-moment decision affects the long-range horizon, and every far-reaching decision has an immediate impact. In the Harvard Business Review, Rosabeth Moss Kanter notes that effective leaders are constantly and deliberately choosing which lens is the appropriate according to the situation, as they recognize the ripple effect that their decisions have on their organizations, the industry, and the entirety of the ecosystem. Indeed, they understand interdependence.

Bringing wisdom and compassion to consider the past-present-and-future requires what Bain calls centeredness, a “state of greater mindfulness, achieved by engaging all parts of the mind to be fully present…the precondition to using one’s leadership strengths effectively.” Centeredness exercises the neurobiological muscles of focusing in on the trees and focusing out to the forest. The more that leaders build these muscles, the more their brains are primed for deliberate, intentional, and expansive thinking. A charismatic visionary or a technical genius is great; a charismatic visionary or a technical genius with centeredness is powerful.

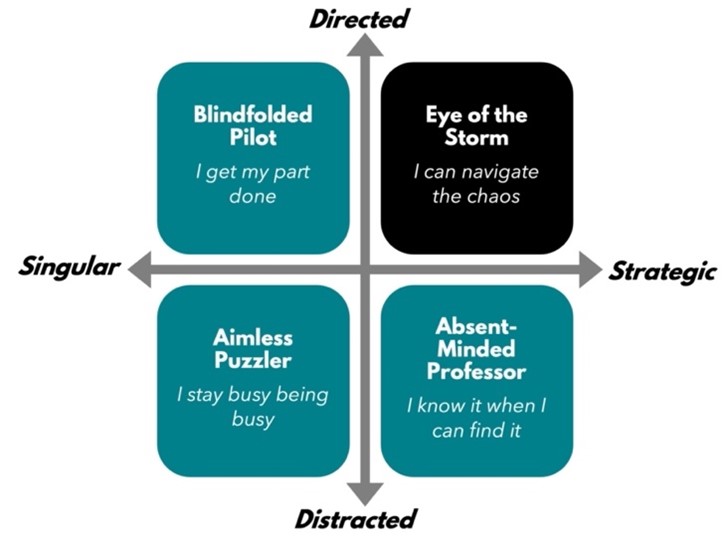

Figure 1: Intentional Focus

Centered leadership can be seen across two dimensions: 1) how focused (directed) or scattered (distracted) our attention is to the present moment, and 2) how broad (strategic) or tunnel-visioned (singular) we are about what is happening around us. Leaders can be extremely effective in getting tasks completed if they are highly focused, but if they are tunnel-visioned, they may become overly reliant on the status quo or ignore critical signals of impending change. Or, they may be susceptible to becoming scatterbrained geniuses or falling into the trap of busyness. When leaders are centered, they choose their focus and are attuned to the environment.

Purposeful Play

Second is purposeful play. After all, centeredness alone isn’t sufficient to strategize and execute on vision with broader community and global impact. Those who embrace purposeful play invite experimentation, iteration, and prototyping. Margaret Wheatley and Myron Kellner-Rogers noted that “playful tinkering requires consciousness.” There is a discipline to play – it requires focus and concentration and being aware of everything that is happening and to “respond with minimal hesitation.” The more self- and other-aware we are and present to the current environment, the more choice we create. Leading thinkers and organizations like LEGOTM understand this. In fact, research shows that scarce or limited resources result in greater creativity and innovation.

Play also allows for leaders to acknowledge the absurdity of challenging situations and offer space to imagine possibilities with a dose of healthy humor. Robert Half found that 91% of executives believe humor is important for career advancement and 84% believe it enhances job performance. In his Harvard Business Review article, Fabio Sala found that executives rated as “outstanding” used humor twice as often per hour than those rated “average.” Compassionate leaders know that going beyond the temporal state of happiness to the more sustainable state of joy is where they are more able to heal divisions and act. In their Harvard Business Review article, Brad Bitterly and Alison Wood Brooks note, “abundant benefits await those who view humor not as an ancillary organizational behavior but as a central path to status and flourishing at work.”

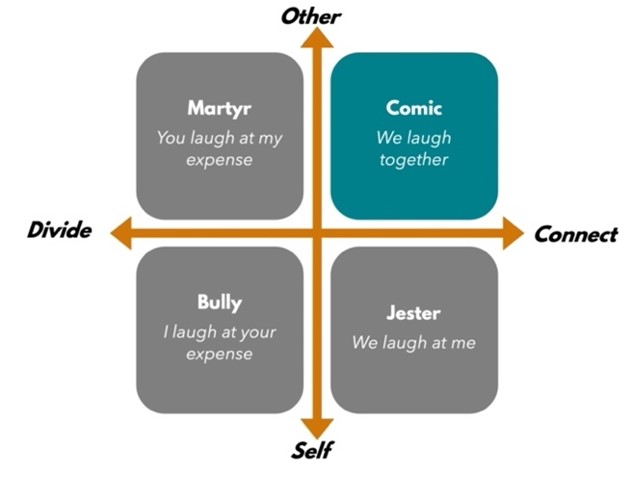

Figure 2: Purposeful Play

However, not all humor is created equal. It can be seen on two dimensions: 1) how we unite (connect) or separate us vs them (divide); and 2) how we direct the joke at the expense of ourselves (self) or someone else (other). While self-deprecation (martyr) or mean-spirited (bully) humor is divisive, research from Harvard and McKinsey shows that when leaders use humor to connect, they unite the entire group in shared laughter. Jennifer Aaker and Naomi Bagdonas’s research that appropriate humor builds trust, positive relationships, problem-solving skills, capacity for perspective-taking, creativity, and wellbeing have translated into a course at Stanford GSB on humor in the workplace. Teams that take an approach of purposeful play are more ready to face the continually changing landscape and take a more proactive approach to the inevitable changing tides.

Active Agency

Third is active agency. While centeredness requires intentional focus and play, leaders must embrace their agency, or power to act, particularly as in the face of change. After all, while some transitions may be more tumultuous than others, the one constant is that leaders are always in a state of transition. Rather than explaining everything as forces happening to them and abdicating their responsibility, leaders who have an internal explanation of control are better able to mitigate fears of uncertainty or embrace failure.

Figure 3: Active Agency

Leaders can map how agile they are on two dimensions: 1) how much they focus on what they can (control) and cannot control (not under control); and 2) how they respond with initiative (active) or inaction (inaction). Leaders may take an active role, but if they overreact on things they cannot control, it can lead to greater anxiety and uncertainty for all. Or, they may bury their heads in the sand and abdicate any responsibility. Leaders who actively focus on what they can control and influence are nimbler to respond with choice and intention.

Even through discomfort and uncertainty, leaders with a mindset for centeredness constantly ask: "what’s the opportunity?" As Frederic Laloux mentioned, “change is a given, it happens naturally, everywhere, all the time” in an interdependent ecosystem in which individuals, teams, organizations, and systems also sit.

To explore centeredness, you may want to investigate these questions:

- What will help me to choose my attentional focus in the moment?

- When might I use purposeful play to connect with others?

- What’s the opportunity to take initiative and influence?

Intentional focus creates the container, purposeful play gives it life, and agency to act reinforces. Centeredness enables leaders to stay present with spaciousness while simultaneously investigating the details of the past to experiment for the future.