By Belinda H.Y. Chiu

06 September 2022

Creating value requires leaders to speak up when things go wrong, have a point of view even when it’s not what “sounds good,” and make tough decisions that impact many. This requires leaders to have the courage, the second part of the Compassion Strategy, to stand firm with clarity. As we noted in the first of this series, the Compassion Strategy includes:

- Centeredness: intentional focus + purposeful play + active agency;

- Courage: authentic integrity + healthy conflict + compassionate candor; and

- Curiosity: shared connection + improvisational paradox.

When leaders strengthen their capacity for centeredness, they can be more intentional about what and how to act in a way that is most appropriate and impactful to a situation. It cultivates their courage to show up as their authentic selves and commit to what matters to them. While courage is often mistaken as being fearless, it is about acting even when fearful. Courage — authentic integrity while embracing healthy conflict and compassionate candor — enables leaders to face the good, the bad, and the ugly.

First, when leaders display courage, they make decisions and communicate with authentic integrity. They are less likely to be swayed by external factors, such as money, power, or ego. They know their core values and purpose, what Bill George calls their “true north.” They know when they say ‘yes,’ and when they say ‘no.’

Contrary to public misperception, compassion is not about rolling over, being nice, and saying ‘yes’ to everything and everyone. By asserting their power and setting boundaries, leaders who lead with compassion build the courage to say no while creating connection and dismantling barriers. As William Ury articulates with the “power of the positive no,” leaders who know their authentic needs and values have greater choice in how their integrity impacts others.

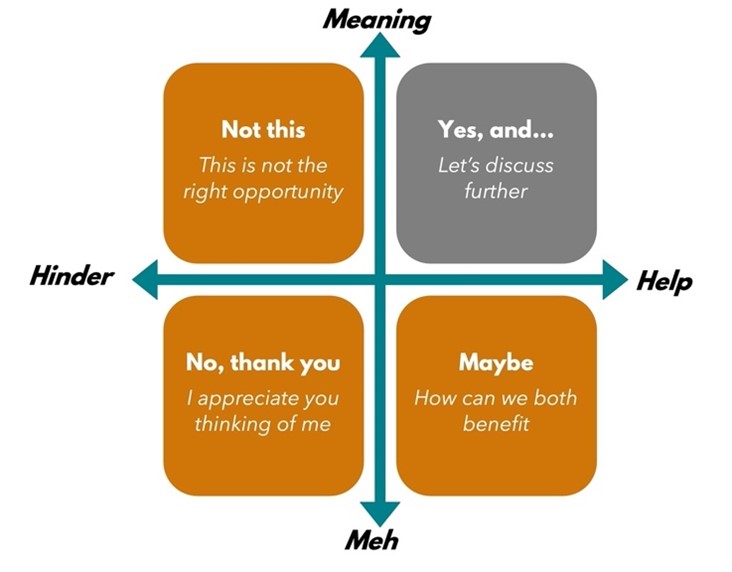

Figure 1: Authentic Integrity

The anatomy of authentic integrity allows us to choose a wise 'yes' over an ill-considered one and can be seen on two dimensions: 1) how much the decision or ask is positive (help) or detrimental (hinder); and 2) how much the decision or ask is true to what matters to us (meaning) or not (meh). When leaders lead with courage, they recognize when the timing is not right, it is not a high priority for them, or when their values or integrity are compromised, and and are willing to say 'no.' This allows them to say ‘yes’ to opportunities that align with their authentic selves.

Second is healthy conflict. Compassion is also not about faux harmony with the self and others. What courage asks of leaders is to take a stand and embrace interpersonal conflict. In a survey of 700 senior executives, RHR International found that 87% of top-performing teams had leaders who were willing and able to handle conflict effectively — not so much with the non-high performers. Studies suggest that healthy conflict resolution requires empathy, including leaning into the discomfort of disagreement, attending to and feeling with the other person, having emotional self-awareness, and being motivated to resolve the conflict. Healthy conflict means recognizing our default conflict style and being nimble enough to choose the most appropriate one for the moment.

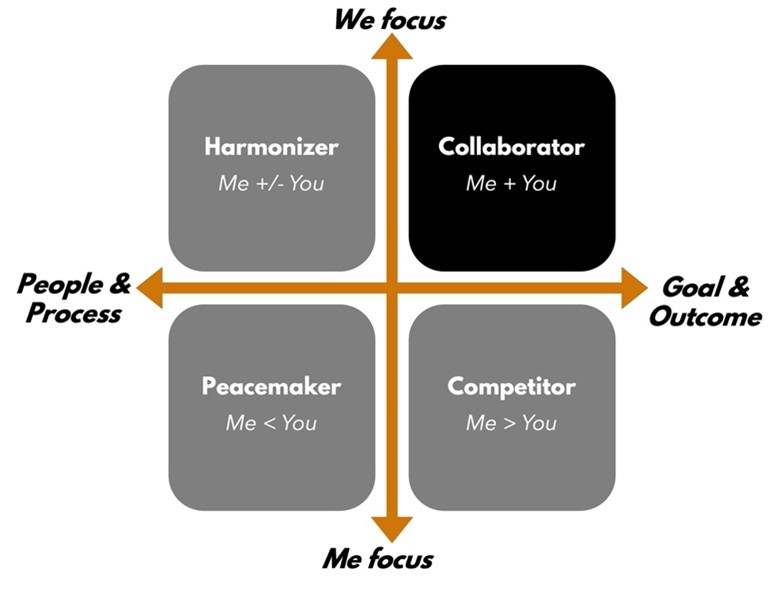

Figure 2: Healthy Conflict

Inspired by the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Inventory, conflict styles can be viewed across two dimensions: 1) how focused on the what (goal and outcome) or the how (people and process); and 2) how focused on the relationship ('we' focus) or the self ('me' focus). If not aware, leaders may end up in situations where both sides are mutually dissatisfied, bully others for the win, or placate their own needs. Or they may focus on the goal and the relationship to seek ways where both parties maximize their winnings. Recognizing the appropriate style builds the courage to embrace healthy conflict.

Third is compassionate candor. After all, while effective conflict management requires the courage to face the truth, even when it is the leader who is causing the conflict or doing the offending, people demand honesty and authenticity from their leaders. Leaders who consistently demonstrate courage work on being honest with themselves and, by so doing, give permission for others to do the same.

But the reality is that when it comes to being honest with others, most of us find it discomforting. Particularly in the last few years, many leaders have faced a reckoning with hypocrisy and half-truths. People follow leaders and organizations who share hard truths with kindness, even if that truth is “I don’t know when this will end,” not mistruths wrapped up in sugar-dripping niceness. This requires leaders to have the courage for candor.

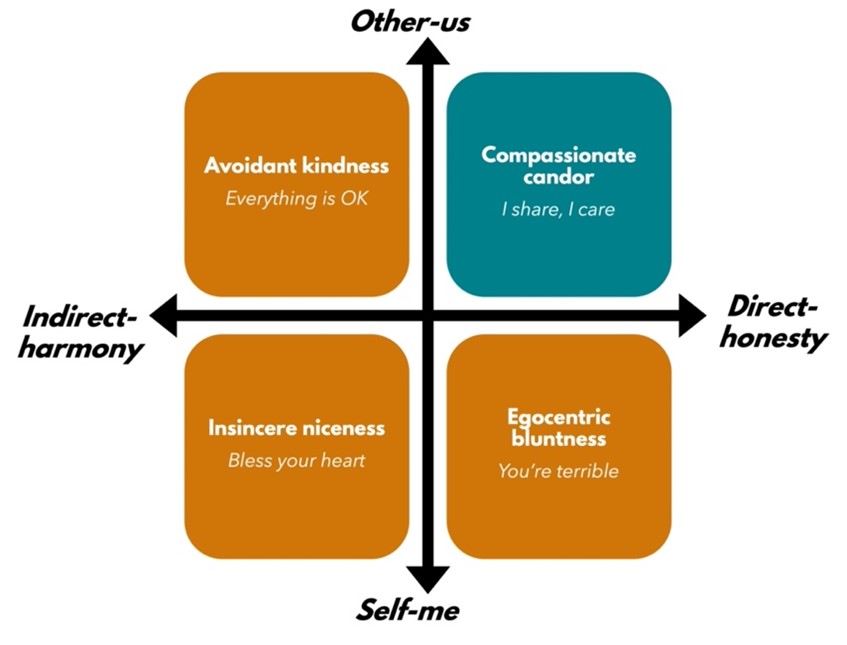

Figure 3: Compassionate Candor

Compassionate candor can be seen across two dimensions: 1) how focused we are on honesty (direct-honesty) or on harmony (indirect-harmony); and 2) how focused we are on the relationship (other-us) or ourselves (self-me). Without the courage to be candid, leaders may make themselves vulnerable to issue-avoidance, over-the-top bullying, or passive aggressiveness. However, when they are other-focused and willing to be open, vulnerable, and transparent, they are better able to address reality and hold themselves and others with kind accountability.

To explore courage, we suggest you explore these questions:

- What will I say no to, in order to create more opportunities to say yes?

- What conflict style is appropriate, in which moments, to embrace healthy conflict?

- What will promote a culture of compassionate candor?

Courage enables leaders to be honest with who they are and what matters to them, setting boundaries and approaching conflict with compassionate candor. Doing so allows them to make wiser decisions not only for themselves but for others to flourish.